Note: This is actually, by all means, an academic contextual analysis I recently wrote. I’m keeping it the way it was when I submitted it because I feel the direct quotes and work cited are valuable for exploring the representation at hand. Nevertheless, after completing it, I wanted to share it in some capacity. Hope you enjoy – Dan

Minority depiction and representation within media has always been a contested conversation for multiple reasons. Most importantly the general rule when it comes to representation is people want to be able to see themselves depicted within media and foremost in a positive and explorative aspect. Whether it be the depiction of race, gender, or sexuality, there is a need for global representation of all minorities and tolerance of such perceived differences. The portrayal of the LGBTQ community is just one subgroup to be represented across a spectrum of different opinions and perceptions. Historically speaking, the LGBTQ community has been presented negatively in media. Nevertheless, by the turn of the 1990s, depiction of the community has grown significantly and most impressively within the medium of television. Since the 1990s, LGBTQ representation has increased substantially in size and scope within television. With the past 10 years alone, the latest GLAAD report shows that from 2006 to 2016, the percentage of LGBTQ characters on television has grown from 1.3% to 4.8%. With LGBTQ representation on television never being higher than it is currently, such representation is making an impact in today’s media landscape. While the current state of LGBTQ representation within television has never been greater, such representation is far from perfect. Being instrumental to how the LGBTQ community is represented and perceived, in addition to how it directly influences the community itself, television is one of the most important cultural landscapes LGBTQ people currently have.

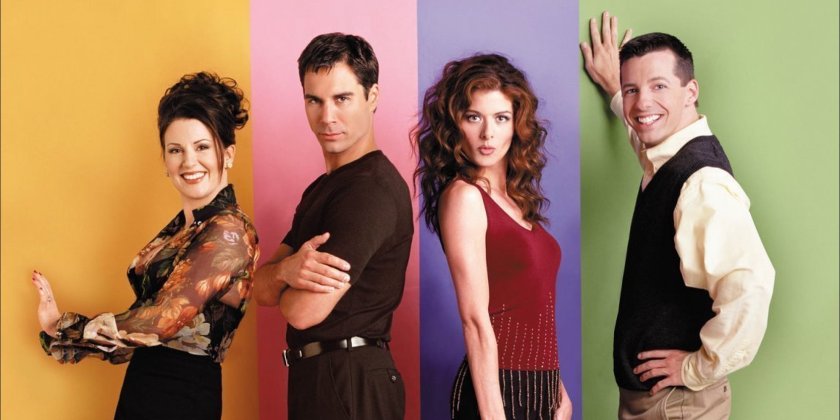

To really address the current state of the LGBTQ community within television, it is important to first take a step back and look at the real turning point for representation with the debut of Will & Grace (1998-2006). Before Will & Grace, very little depiction of LGBTQ life could be found on television. The earliest examples could be found with high school teen, Ricky on My So-Called Life (1994-1995), AIDs victim, Pedro Zamora on MTV’s The Real World: San Francisco (1994), and Ellen DeGeneres coming out in her own sitcom, Ellen (1994-1998) in 1997. As Zachary Snider would show within his essay published in the book, Queer TV in the 21st Century: Essays on Broadcasting from Taboo to Acceptance, Will & Grace would go on to make gay couples on television okay. Snider most importantly highlights the show’s “clever trickery” in making gay lifestyle seem more acceptable:

While the imposition of traditional gender roles in real life can certainly limit one’s identity composition and the healthiness of a same-sex relationship, on television, gender-role representations are safe. They are marketable . . . However in the case of Will & Grace, the series engaged viewers for years with heteronormative conventions; hooked these viewers with its characters, silly plotlines, and uncommon character relationships; and then, in its last couple of seasons, abandoned heteronormativity for its characters’-namely Will’s-happiness. (Snider 205)

Will & Grace (1998-2006)

By following the general rules of the standard sitcom and making the gay-character likable within a heteronormative frame, Will & Grace took off successfully. Will & Grace rode off the classic misinterpretation and misunderstanding dynamic between such character identities and in return created one of the most successful sitcoms around the turn of the century. Presenting the modernized urban family between the four characters, viewers were watching a show that prominently featured two gay male characters whether they really acknowledged it or not. Despite the show’s success throughout eight seasons, the depiction of Will and Jack was not always positive. As Snider points out, Jack was always seen as being portrayed as a “cliché, flamboyantly gay” and Will was often “not gay enough.” Nevertheless, by the time Will & Grace came to an end, teenage shows such as Dawson’s Creek (1998-2003) and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) both prominently featured gay characters, and cable pursued the first real adult gay-centric shows of Queer as Folk (2000-2005) and The L Word (2004-2009).

Conversely, the LGBTQ community has a lot to thank for with Will & Grace. When Will & Grace came to an end in 2006, LGBTQ representation was at a total of 1.3% according to the ’06-’07 GLAAD report. Regardless, there was a total of 25 LGBTQ character regulars in 2006. No longer were gay males being featured as the stereotypical flamboyant queen as the singular representation on television. Jump forward ten years later to 2016 and representation has grown significantly. Beyond just the overall percentage going up three percent, it’s important to look specifically at the exact representation itself. Most prominently going beyond just the gay male, Lesbian/Bi/Trans representation has grown from a 40% share of LGBTQ characters in 2006 to 53% in 2016. Most importantly the community can see a total of 16 Trans characters (regulars and recurring) within television today. Ten years ago, there were no Trans characters to speak of within television. Still, representation within television is far from perfect. From the lack of intimacy presented on screen, the use of “queer-baiting,” and the recurrence of killing bisexual and lesbian women characters, some areas require significant revision and consideration.

Despite the increasing popularity and representation of LGBTQ characters, the presentation of real intimacy between such characters remains a bigger issue. Take for example one of the biggest hit sitcoms of the past decade, Modern Family (2009-present). Known for featuring a diverse extended family, Mitchell and Cameron are relatively presented as sexless in comparison to the other adult couple counterparts found on the show. In the Buzzfeed article, Television May Be Embracing Gay Characters, But Where Is The Same-Sex Intimacy?, Louis Peitzman chronicles how even today presenting gay sexuality is relatively harder to get across than heterosexual forms of affection:

The hard truth is gay sexuality is considered inherently more risqué than heterosexual sexuality. And that’s not limited to sex — a kiss between a man and a woman is expected on nearly every TV comedy or drama, but a same-sex kiss continues to give pause. (Peitzman)

Due to the non-heteronormative nature of LGBTQ intimacy, a kiss between a same-sex couple serves as a risk. Even the MPAA rating system has been found to rate films with gay content more harshly than those who don’t. It is this conservative mindset that holds back LGBTQ sexuality, out of the fear of protest or losing viewership. In Modern Family alone due to a lack of intimacy and the constant use of nagging between the couple, it can almost be perceived that Cameron and Mitchell do not even like each other and that serves as an issue when presenting a family dynamic and positive representation.

Modern Family – Jesse Tyler Ferguson as Mitchell and Eric Stonestreet as Cameron.

Nevertheless, there is, even more, to look at by delving into how the specific camera angles used within network television can shortchange the entire experience of LGBTQ intimacy. After internet protests towards the lack of any exhibited kissing between Cameron and Mitchell on Modern Family, the show would present its first same-sex kiss in the season two episode, “The Kiss.” In the journal article, It’s (Not) in His Kiss: Gay Kisses and Camera Angles in Contemporary US Network Television Comedy, Alfred L. Martin Jr. documents the exact portrayal of the kiss. Discussing the over-the-shoulder angle (OTS), Martin presents the potential disappointment to be found in the shot:

Just as an OTS obscures the speaker during a conversation with another character, in this instance, the OTS obscures the two men’s lips touching during the kiss. When the kiss between Mitchell and Cameron occurs, it is, according to the New York Times’ Dave Itzkoff (2010) a “blink-and-you-missed-it peck in the corner of the screen, unassuming and unobstructive, as some people genuinely prefer their intimacy to be.” (Martin 159)

Even though Modern Family gave into what the LGBTQ fans were asking for, both viewers and critics were disappointed with the execution. As both Peitzman and Martin show within their observations is the lack of queer intimacy isn’t just a sole issue with Modern Family but an issue to be generally be found in any network show featuring LGBTQ characters. The only place where real intimacy can be found is on cable and most likely upon shows that find themselves being rated TV-MA. Despite television being willing to embrace representing and showing LGBTQ characters, they are missing part of the picture by also not embracing such intimacy.

Just as much as there is a need for LGBTQ intimacy, there is also a fine line to be crossed with what is done with such representation. In Kelly Kessler’s journal article, They Should Suffer Like the Rest of Us: Queer Equality in Narrative Mediocrity, she argues that by giving LGBTQ characters a focus but nonetheless, a heteronormative one, you are submitting such characters to television mediocrity:

In short, I think TV writers are writing just as preposterously, wonderfully, formulaically, and at times just plain badly for GLBTs as they are for everyone else. Stereotyped gays, overrepresented young and white gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and feuding queer couples abound, but check out the straights on the tube and you’ll find that they look pretty similar. (Kessler 139)

Arguing that such issues of representation should not be focused on the amount of LGBTQ characters seen on screen but the quality presented within each one. Kessler primarily concludes that it is the process of making well-rounded and intriguing LGBTQ characters that ultimately makes the difference. At the same time when such critically received gay-centric shows make the attempt to be explicitly queer, very few are able to make it far, commercially.

In the past three years, four adult LGBTQ-centric shows have all come and gone away. HBO’s Looking (2014-2015), BBC’s companion shows Cucumber (2015) and Banana (2015), and ABC2 (Australia)’s Please Like Me (2013-2016) have all lived out their short lives despite positive critical reception. The BBC companion series of Cucumber, Banana, and Tofu (a web series counterpart) were significant on their own for being interconnected and airing together on the same night during their run. Created by Russell T. Davies, the same show creator as the first mature gay-focused show, Queer as Folk (UK 1999-2000), the three shows were heavily anticipated. Cucumber told the story of a forty-six-year-old gay man, Banana was an anthology series featuring a self-contained focus on different LGBTQ characters within each episode, and Tofu was a queer talk show. The three shows together saw prominence for nearly every spectrum of the community. Nevertheless, the crew and cast were adamant that the show was more than just “gay.” During a cast and crew interview with the London Gay Times, reporter John Marrs documented such sentiments held towards describing the show as more than just “gay”:

If there’s one sentiment we’ve found shared by every member of the Cucumber and Banana cast that we’ve spoken to – and one we hope you’ll agree with as you read these pages – it’s that Russell’s return shouldn’t be seen as a ‘gay series’, or pigeonholed as such. But, in fact, should be recognised for what it truly is – a celebration of life and living, love and lust, sex and sexuality, in whatever form that may take. (Marrs)

Regardless after premiering and achieving critical success, none of the three counterpart shows were picked up for another series. Despite the novel intentions to create LGBTQ-centric television, the US version of Queer as Folk and The L Word still remain the only real past successes.

With a need for more LGBTQ representation and quality characters, several shows have also gone down the wrong path in attracting such a community. BBC’s Sherlock (2010-present) serves as a show that potentially uses “queer-baiting.” Defined as a tactic, intentional or not, to attract viewers through the use of homoerotic subtext without actual such characters being queer themselves, the internet is quick to dig into the possibilities of such subtext. Particularly within an online community, the psychological process that can be found in such deliberate fandom can prove to be incredibly taxing and often hurtful towards those who identify as queer. Such invalidation is depicted in Cassidy Sheehan’s research poster, Queer-baiting on the BBC’s Sherlock: Addressing the Invalidation of Queer Experience through Online Fan Fiction Communities:

In order to undergo “healthy human development,” queer individuals find sources to mirror and validate their identities. When lacking other sources, media such as television may be used. According to Henry Jenkins, “fans construct their cultural and social identities through borrowing and inflecting mass culture images. (Sheehan)

Presenting the negative effect whether intended or not by the writers that “queer-baiting” can withhold, television writers should be conscious of the potential adverse effects to be found within such tactics and avoid employing them at all costs.

A far more dangerous, complicated form of “queer-baiting” can be found most recently in the “bury your gays” trope found in multiple television shows of late. Last year, the death of a lesbian character on the CW’s The 100 (2014-present) sparked controversy for being unnecessary. Due to internet outrage, newly public protest went towards the “bury your gays” trope that has found 95 lesbian and bisexual women characters being killed off within American television over the past forty years. As June Thomas discusses in her article, Why Is TV Killing Its Queer Women? for The Advocate website, she speaks to the importance of the awful effect that the trope can truly carry:

Why does this matter? Because it’s natural for viewers to project themselves onto the people they spend time with every week. It’s downright depressing when a particular type of character — one who’s like you in a fundamental way — keeps meeting the same miserable fate. If fictional lesbians are doomed to die, you can’t blame real women for wondering if they can ever be happy. (Thomas)

Black Mirror‘s San Junipero serves as an almost-antidote to the “bury your gays” trope

In this current “anyone can die” political sphere of television, writers must realize that there can be a profound impact found within eliminating a show’s minority fueled characters and how they are perceived. Within an already cis-gendered, typically white, heterosexual world, characters that differ from the typical should be living to see another day instead of being casted to the side or thrown away.

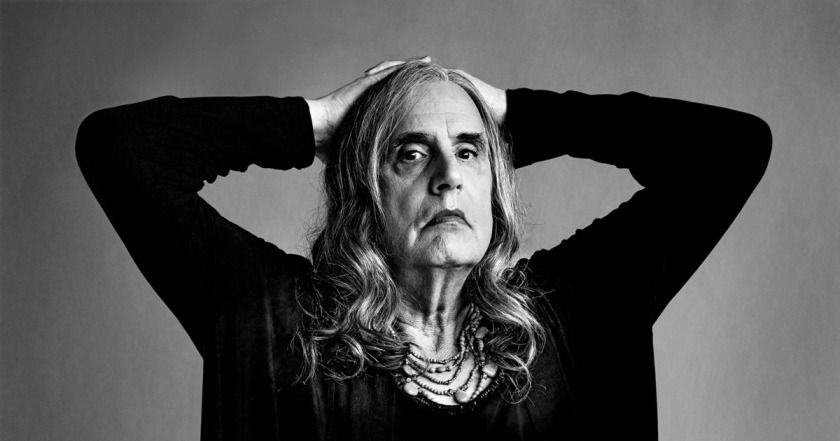

Regardless of the dangerous consequences to be found inside the mishandling of LGBTQ representation within television, there still is groundbreaking representation to be found currently. Most significantly within Orange is the New Black (2013-Present) and Transparent (2014-present). Both shows have in the forefront depicted Trans characters along with featuring multiple same-sex and queer relationships. Transparent, especially today serves as one of the most critically well received and talked about television shows currently on air. In Amy Villarejo’s journal article for Film Quarterly, JEWISH, QUEER-ISH, TRANS, AND COMPLETELY REVOLUTIONARY: JILL SOLOWAY’S TRANSPARENT AND THE NEW TELEVISION, she asserts Laura Mulvey’s theorization of the “female gaze” and commends the show for its truly auteur quality:

Countering this dominant arrangement of the gaze, Soloway ensures that Maura is never objectified by the camera, not once, during the entire first season of Transparent. She is never looked at with judgment, which is to say that the camera’s look at Maura—not Mort, but the emerging Maura—is never aligned with a character, nor a spectator, who would misrecognize, dismiss, judge, or mock her. (Villarejo)

Jeffrey Tambor as Maura in Transparent

Villarejo clearly states that by the show’s standards by featuring such subverting of the “female gaze” typically casted within television and film, Transparent is truly doing something on television that hasn’t been seen before and can be seen as radically revolutionary. Through the viewer’s eyes, Maura who starts transitioning between gender well into her 60s is seen, recognized, and understood. By never questioning or objectifying her actions, show creator Jill Soloway is creating a “film work for trans emergence.” This form of new Trans representation and acceptance has helped significantly provide a voice for the community but also provide a window for those who have subjectively ever felt different. Ultimately seeing where television as a whole and LGBTQ representation continues from this point will be fascinating to witness.

Due to real Trans representation being so new to fictionalized television, very little studies have been conducted towards the reception and the possible change in perspective such depiction can hold. However, a similar, uncanny movement can be found with LGBTQ youth depiction. Significantly even animated children shows such as The Legend of Korra (2012-2014) and Steven Universe (2013-present) have depicted same-sex relationships and other gender associations. In addition, teenage dramas have grown significantly in importance and recognition. With The Fosters (2013-present) on ABC Family/Freeform, the show has become a media milestone in the depiction of a multi-ethnic family and multiple LGBTQ characters. One of the show’s most significant efforts was depicting the youngest televised same-sex kiss between two boys at the age of 13. As a result of such a milestone, a scientific study with 469 participants between the ages of 13-21, depicts the emotional involvement and attitude found with such depictions. What the study went on prove was that the majority of the straight and LGBTQ youth held different feelings and attitudes towards the depiction. While the majority of the straight audience, especially within the influential age period with stigmas felt “disgust” towards the depiction, the LGBTQ youth clearly felt different. As both Traci Gillig and Sheila Murphy present within their study, LGBTQ youth was able to ascribe emotionally to such representation:

The findings suggest that LGBTQ youth saw themselves reflected in the portrayal of two young gay characters coming to understand their identity, and these participants strongly experienced the positive emotion of hope, an elevated sense of mental energy, and pathways for goals. (Gillig and Murphy 3843)

In spite of the stigma’s held by the majority of the heterosexual youth in the experiment, the LGBTQ youth response ultimately presents the importance such representation holds within a medium such as television. Television as a form of entertainment can transcend and provide meaning for young people and adults alike in presenting and representing a minority group.

Despite several controversies, LGBTQ representation exists as a significant and forward movement within television. As representation within numbers continues to increase, so does the ways in which television is able to depict different spectrums of the community. Nevertheless so much within the LGBTQ community remains to be explored within television and improved upon. Spectrums such as asexuality remains to this day as a barely touched subject within television. Tropes such as “queer-baiting” and “bury your gays” still prove to exist today, holding an incredibly negative effect. Very few LGBTQ-centric shows receive the commercial success they need to thrive upon, and those networks shows with LGBTQ representations play it rather conservative within depiction. While the LGBTQ community faces such issues and current representation is by no means to be found perfect, it is significant to look at the growth the community as a whole as faced within the past twenty years. Most importantly how representation has gone past one single stereotype to presenting a huge array of characters and issues. With Orange is the New Black and Transparent as the current flag holders for such representation and setting the next landmarks to expand upon, how television significantly grows and develops within the next twenty years; nonetheless, ten, for the LGBTQ community will be fascinating to witness. What is known for the time being is the LGBTQ community within television will not be going away or diminishing anytime soon and will only continue to be a relevant social issue as long as television remains such a powerful and available institution.

•••

Works Cited

Gillig, Traci K., and Sheila T. Murphy. Fostering Support for LGBTQ Youth? The Effects of Gay Adolescent Media Portrayal on Young Viewers 2016th ser. 10 (2016): 3828-850. Web. 02 Feb. 2017. <http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/viewFile/5496/1741>.

GLAAD. Where We Are On TV ’06-’07. N.p., 2006. Web. 02 Feb. 2017. <http://www.glaad.org/sites/default/files/2006-07%20Where%20We%20Are%20on%20TV.pdf>.

GLAAD. Where We Are On TV ’16-’17. N.p., 2016. Web. 02 Feb. 2017. <http://glaad.org/files/WWAT/WWAT_GLAAD_2016-2017.pdf>.

Hart, Kylo-Patrick R. Queer TV in the 21st Century: Essays on Broadcasting from Taboo to Acceptance. Jefferson, NC: McFarland &,, 2016. Print.

Kessler, Kelly. “They Should Suffer Like the Rest of Us: Queer Equality in Narrative Mediocrity.” Cinema Journal 50.2 (2011): 139-44. Academic Search Complete [EBSCO]. Web. 02 Feb. 2017. <http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?sid=97a44c45-3c8f-40c2-8354-35692c038385%40sessionmgr4007&vid=0&hid=4212&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=59533687&db=f3h>.

Marrs, John. “Cucumber Banana Tofu.” Gay Times. N.p., 2015. Web. 01 Feb. 2017. <http://search.proquest.com/genderwatch/docview/1649049770/FA475A19A0E64461PQ/40?accountid=10477>.

Martin, Alfred L. “Itâ™s (Not) in His Kiss: Gay Kisses and Camera Angles in Contemporary US Network Television Comedy.” Popular Communication 12.3 (2014): 153-65. Academic Search Complete [EBSCO]. Web. 02 Feb. 2017. <http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?sid=b31ea904-ae04-46d0-8ac2-5096bcf093a1%40sessionmgr4010&vid=0&hid=4212&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=97376886&db=ufh>.

Peitzman, Louis. “Television May Be Embracing Gay Characters, But Where Is The Same-Sex Intimacy?” BuzzFeed. BuzzFeed Entertainment, 10 Dec. 2013. Web. 02 Feb. 2017. <https://www.buzzfeed.com/louispeitzman/television-may-be-embracing-gay-characters-but-where-is-the?utm_term=.rvqxJ0YRl#.igzJLWd06>.

Sheehan, Cassidy. “Queer-baiting on the BBC’s Sherlock: Addressing the Invalidation of Queer Experience through Online Fan Fiction Communities.” VCU Scholars Compass, 2015. Web. 1 Feb. 2017. <http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1121&context=uresposters>.

Thomas, June. “Why Is TV Killing Its Queer Women?” Advocate. The Advocate, 07 Sept. 2016. Web. 01 Feb. 2017. <http://www.advocate.com/television/2016/9/07/why-tv-killing-its-queer-women>.

Villarejo, A. “Jewish, Queer-ish, Trans, and Completely Revolutionary: Jill Soloway’s Transparent and the New Television.” Film Quarterly 69.4 (2016): 10-22. Web. 2 Feb. 2017. <http://www.filmquarterly.org/2016/06/jewish-queer-ish-trans-and-completely-revolutionary-jill-soloways-transparent-and-the-new-television/>.

A great article showing the public how important it is to represent all members in our communities in positive role models in the media.

LikeLike